Territorial Approach for Sustainable Livelihoods - Example: Territorial Approach for Sustainable Livelihoods: Backbone Approach, DETA Afghanistan

|

Background on AfghanistanAfghanistan’s framework conditions are characterised by the years of conflict and a strong donor driven development. Even though improvements have been made to date with regard to the legal and administrative business environment the economic development institutions provide insufficient incentives for either national or international investors to engage in the Afghan economy. Government institutions are not yet capable of playing a developmental role in a free-market economic system. Furthermore, the private sector is still not organised enough to sufficiently incorporate its interests in the economic reform process.

Background of the DETA programmeThe Global Programme Development-Oriented Emergency and Transitional Aid –DETA offers support to the people in selected areas in Afghanistan where the government faces difficulties in providing the basic supplies and services required for survival. DETA ensures that public services are delivered during periods immediately following emergencies. Support is provided for a limited time period while at the same time promoting self-help capacity at all levels of society and the state. This way DETA encourages the implementation of sustainable solutions based on long-term strategies, while discouraging violent, survival-based behaviour that escalates the initial situation with possible longer-term consequences.

Background on DETA’s Sustainable Livelihoods and Backbone Approach in AfghanistanIn 2003 the Government of Afghanistan and its international partners became increasingly aware that issues and challenges surrounding sub-national governance in Afghanistan would be crucial to national development, stability, and security. To react to these challenges, the government introduced Community Development Councils (CDCs), established under the National Solidarity Programme (NSP) to approximately two-thirds of the villages in Afghanistan. The objective was to enhance the ability of Afghan communities to identify, plan, manage and monitor their own development projects. Through the promotion of good local governance, the NSP worked to empower rural communities to make decision affecting their own lives and livelihoods. Empowered rural communities collectively contributed to increased human security. The programme is inclusive, supporting entire communities including the poorest and vulnerable people. NSP strongly promoted a unique development paradigm, whereby communities could make important decisions and participate in all stages of their development, contributing their own resources. With the support of Facilitating Partners (e.g. certified NGOs, etc) the communities elected their leaders and representatives to form voluntary Community Development Councils (CDCs) through a transparent and democratic process. Figure 1 & 2: Backbone approach, DDF and PDF as instruments for territorial sustainable livelihoods

At the centre of the concept was the labour intensive backbone project - often a larger infrastructure project (compare figures 1 and 2), which was combined with income and employment generating support projects. The allocation and prioritisation mechanism was done through a transparent process as part of the district and provincial development funds. A core development hypothesis of the concept was that the allocation of resources to the two funds would promote and enhance a transparent, equitable and just allocation of resources (i.e. part of good governance process). The PDF was assessed in 2007 and was deemed to be an effective approach not only for introducing capacity development, good governance and transparency but also for coordinating the different German Government Ministries providing funds for the reconstruction and development of Afghanistan. |

|

Applying the Backbone Approach in AfghanistanThe sustainable livelihoods’ approach with the “backbone projects” at the centre is a people centred approach that aims to increase the sustainability of poor people’s livelihoods, especially in a post-conflict or post-disaster setting.

Figure 3: Sustainable Livelihoods elements, impacts and effects The backbone approach is based upon the interaction of:

Photo 1: Example of labour intensive backbone project (important district road) |

|

|

Process 1 Territorial selection of intervention areas:The resource limits necessitated that not all areas in a province could be equally supported. This meant that a transparent selection process was required to determine which districts in the province should be supported initially. The selection of the districts in which to concentrate the activities of the programme / project can be undertaken through a host of different criteria. Each set of criteria applied is designed to reduce the overall number of districts to select from. Ideally, primary data would be collected for the selection process. This was not possible given the resources available (e.g. time, finances and personnel) to collect, analyse and interpret primary data. To optimise use of resources secondary data used included:

Table 1: Selection according to population densities Table 2 Selection according to % population with less than 2100 kcal / per capita

Table 3: Ethnicity in a province

Table 4: Number of donor supported projects in the districts

Table 5: Final overall selection

Process 2: Selecting the backbone project in a district:In the districts that were selected as being the focal districts for the initial intervention areas, a key process was also to select a labour intensive backbone project. Backbone projects could be a rural road, primary irrigation channel, intensive re-forestation, etc. A key in the selection process was to ensure that, as many community members would be able to work on the labour intensive project for a period of 1-2 years. This would then ensure that the communities have work for a defined period of time.

Process 3: Establishing the Development Funds:A key instrument that was developed as part of the approach were the two development funds, namely:

Figure 4: Relationship of volume of funds in DDF and DDF + over time Process 4: Elaborate an operations manual for the DDFThe operations manual for the DDF regulates the entire operational process for the DDF. The manual defines the organisational structure (i.e. commissions, decision making bodies), the application, approval and management of the development projects as well as administrative accounting, reporting and monitoring functions. The manual should be short and precise and serves as the basis for addressing all administrative and management issues related to the DDF, including DDF+ (examples of such manuals can be found under “Development Funds” on the Methdodfinder website). A similar manual and approach was also developed for the PDF.

Process 5: Community mobilisationCommunity mobilisation is a process of engaging communities through participatory methodologies with the objective of giving them the confidence to take responsibility for identifying potentials and solving problems that hinder them from tapping existing potentials. The community mobilisers from DETA actively supported the CDC and Shuras (e.g. local traditional councils) in all aspects of community mobilisation required for the projects, which the community had applied for. The mobilisers also looked into potential conflicts within the community and sought ways of addressing these prior to approving and implementing any projects to be supported from the DDF.

Process 6: Call for proposalsCommunities in North East Afghanistan were informed via the district authorities, the Department of Reconstruction and Rural Development (DRRD) and through the GTZ that CDC and Shuras could apply for support for their development projects as part of the DDF. In fact, all commission members have the right to inform the communities about DDF. Standard application forms based upon the already functioning National Solidarity Programme were provided to communities. The completed applications were then forwarded to the DDF secretariat for processing and assessing.

Process 7: Assessment and analysis of applicationsA very important process is the assessment of the applications. The assessment of the community projects was undertaken by both the DETA social mobiliser, gender, agricultural and engineering experts, depending upon the type of project. The work is intensive, time consuming and resource intensive (logistics of reaching the remote communities and also costs involved in technically assessing the project proposals). Once the technical and social assessment of the projects has been completed key data from the project proposals were inserted into an assessment matrix.

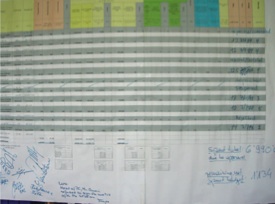

Process 8: Assessment matrixUpon completion of the assessment by the DETA experts (e.g. engineers, community mobilisers, gender or agricultural specialists) the information of the projects to be presented for approval by the DDF are inserted into an assessment matrix. The assessment matrix is part of the transparent presentation and decision-making system. In order to be able to compare larger and smaller projects, an efficiency criterion is used. Key factors such as costs, or benefits are divided by the number of direct beneficiaries, giving a cost/per beneficiary ratio. Thus the expected costs and performance of projects of different size can be better compared with each other. Figure 5 provides an example of the assessment matrix.

Table 6: Example of the DDF Decision-making matrix Process 9: DDF approval sessionParticipatory approaches for approving development programmes has been quite a novel in Afghanistan, especially the fact that the total resources available that will be allocated is announced in advance. This allows for a matching of resources with those projects that receive the highest priority in the decision-making matrix. The number and value of projects almost always exceeded the available funds, hence the need for prioritising the projects. The projects are presented and discussed at length. Representatives from the districts attend the sessions, thus allowing for immediate answers to be provided to any questions the commission members may have. Pictures 2-4 highlight how the commission members discuss and reach decisions on the projects to be funded by the DDF.

Photo 2: DDF Commission meeting

Photo 3: Illustrating a point

Photo 4: All members have signed the final results on the decision-making matrix

|

|

Process 10: Contracting and implementingA joint contract between the CDC or Shura and the DETA-GTZ projects is signed upon approval of the projects. The next step involves getting the community to provide their contribution in-kind for the project. Unfortunately, this often proves to be a very cumbersome and time-consuming activity. Experience shows that the ownership of the projects significantly improves through the community contribution.

Process 11: Technical and financial monitoringThe DDF Secretariat and experts continuously advice, support and monitor the communities / organisations implementing the approved projects. A project folder for each project is provided as part of the project documentation and monitoring process. The project folder contains all information related to the project, including copies of the implementation agreement, list of contributions of the community members, as well as advisory notes written by the technical experts during their monitoring visits. The project folder is accessible to all members of the community and is designed to ensure a maximum of transparency on all aspects of the project. The folder also provides the basis for accounting and reporting the projects to the donor and the German taxpayers. Photo 5: Satisfied male members of the community

Photo 6: On-the-job training

Process 12: Completion, maintenance plan and formal inauguration:Maintenance of newly created assets is essential. It is therefore important that a maintenance plan is developed and agreed upon by the community and in some cases also with the district authorities. The maintenance plan should be as cost-effective and realistic as possible. Thereafter, the formal completion and handing over the project within the community / organisation can be undertaken. Project completion has to be documented by the DDF Secretariat. The formal handing over of the project is often a reason for combining this with a local festival or enabling politicians and donor representatives to participate. |

|

BMZ / GTZ, Schiffer, Kornelius; 2009; Capacity Development for Community Development Councils in Northeast Afghanistan; Development Oriented Emergency and Transitional Aid Programme Related Methods:

Development Funds |