|

|

Step 1: Working definition of fragility and fragile states

The objective of this step is to define and initially agree on fragility. A good starting point is the OECD-DAC definition. The definition highlights two important aspects; a fragile state is one that lacks the “political will [or] capacity to provide the basic functions for poverty reduction” and “development” and that a fragile state cannot “safeguard the security and human rights of their populations”. The two sentences contain what fragility is, why it is a problem and how it should be addressed. Reducing complexity to key issues puts into perspective the emphasis on context as a starting point.

For the last twenty years, donors and development organisations have increasingly seen the state as being the central force for achieving progress for poverty reduction, peace building and conflict transformation. Therefore the BMZ (Federal Ministry for Cooperation and Development) has devoted significant attention and resources to strengthening the role of the state.

Similarly, the post conflict/ post disaster projects has also developed approaches for engaging the state in the context of fragility. An important recognition that has emerged is that the social and political contexts must be analysed in-depth, which also includes determining the exact roles and incentives of the different actors (including government officers, civil society actors, and private business persons).

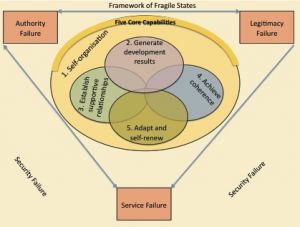

A recent study (Stewart F, Brown G, Nr. 3, June 2010 Fragile States, CRISE, Oxford) distinguishes between three main types of failure at country level. The approach provides an appealing and practical basis for categorising and deriving scenarios for fragile states:

- Authority failure, where states lack the authority to protect their citizens from various kinds of violence

- Service failure, where states fail to ensure access to basic services to all citizens

- Legitimacy failure, where there are no accountability mechanisms between the state and the population

The three forms of failure mentioned above inherently contain a further important form of failure namely:

- Security failure, where basic human security is not provided for and ensured by the state.

What is important is that fragile states are rarely fragile in all aspects and typically possess some important levels of capacity. Furthermore, fragility may be quite significant in some parts of a country and not in others. Fragility may exist where rebel movements dominate or where the state is absent, without the state as such being fragile. In many countries, the presence of the state is much more felt in the capital and other major cities, while remote areas experience substantial service failures.

|

|

2. Steps for assessing capacity of state administrationsBackground on local state administrations

Traditionally, the functioning of a Government administration has been categorised into national, sub-national (provincial or regional) and local. Local state administrations are those bodies that administrate an area or small community such as village, town or a city. The structure of the division of functional responsibilities, relations and coordination among the different government levels is critical in determining how effective local self governments can be.

There are enormous variations between the different levels of state administrations in fragile states. Very often there is no clarity regarding how to share the duties and responsibilities between executive and legislative and how civil society and private sector can be involved in the administration and development process. While functions are often delegated to lower levels, the necessary resources to implement the functions are not provided. This phenomenon is referred to as being “empowered but powerless local administrations”.

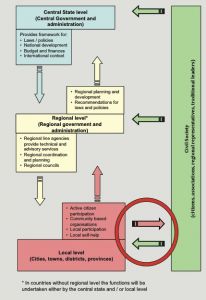

Even though state administrations may not be effective in many countries where post conflict/ post disaster projects projects work, their potential significance remains high. The local state administrations are important in promoting development; this can be termed bottom-up state building”. Figure 2 depicts the interaction and selected functions between the different levels of government and civil society.

Photo 1: Capacity development of government partner institutions (source: GIZ-DETA)

The interaction marked by the circle in figure 2 is an area where the post conflict/ post disaster programmes have the comparative advantage of working with the beneficiaries either through the state (elected) and administrative systems and / or through civil society organisations. The combination of working with both as well as interacting on all three levels of government (national, regional and local) is the key success factor of many projects.

Figure 2: Central - local government and administrations (ideal view)

The salient benefits of working with state administrations include:

- Much of the states responsibilities are actually implemented through the local level administration. At this level it is also a great deal easier to have an interaction between the state and the citizens.

- Local state administrations are often important „door-openers“ for the project to have access to the beneficiary communities.

- The district and commune level is the most immediate contact point between the communities and the state administrations (i.e. “the face of the state”).

- The local level is the only level where a realistic interaction between the state and the citizens can be undertaken above and beyond mere participation in any electoral processes.

- The local level provides a good basis for any meaningful interaction between the state and the private sector as far as economic development is concerned.

- Local administrations are usually responsible for developing, ideally with the participation of the citizens, local development plans. These should be integrated into the respective regional and national plans.

- As post conflict/ post disaster projects generally work directly with the beneficiary communities, a high degree of trust building is required. Post conflict/ post disaster projects works only with those communities where it is actually welcomed by the communities.

- The local level is also expected to implement and realise these development plans jointly with the citizens. This further underlines the importance of the local level.

Step 3: Guiding questions on status of local versus national state administration

- Is there an elected assembly at the local level and how is the state administration linked to the elected assembly?

- How strong is the influence of the national level administration and how is the influence felt at local level?

- How politicised is the state administration?

- Do local or national politicians actively influence decision-making process es at local level and within state administration and how do they do this.

Step 4: Taking up contact with the local state administrations

Although it may be stating the obvious, but when a new post conflict/ post disaster projects starts it is very important to establish good and effective working relationships with the local state administration. The project should also link into any on-going donor coordination mechanisms that may exist in the area. If these do not exist then the project could also try with the counterpart organisation to develop at least an informal coordination mechanism system. This must not result in setting up parallel structures, which would weaken any state aided administration.

There are no defined methods and approaches that can be recommended for this step. Important is that the project develops active networks with the state administrations and other donor organisation working in the area.

Guiding questions on establishing contact with local state administrations:

- Who is the head of the administration?

- What powers does he/she have over the line departments and other state organisations?

- What condition is the administration in (in terms of state of the buildings, level of organisation, etc)?

- How is the administration perceived by the beneficiaries and communities?

- Do they know about the services and functions of the administration?

- What is the general perception by the INGO, NGO and UN organisations of the state administration?

Step 5: Assessing the expected functions of local state administrations

An analysis of existing state administrations at the local should be undertaken. The analysis should examine the functions and areas of responsibility existing at local state administration level and should compare this with the capability (both in terms of human resources and also in terms of funds and equipment).

Important is the need to clarify how the interaction with civil society organisations and community based organisations should and actually is being undertaken. The proposed analysis should not only be aimed at state level organisations but should also include civil society organisations and community based structures. The existing laws, policies and strategies need to be assessed with regard to: suitability, applicability, and consistency for each of the different local self-government levels.

The assessment could include examining income and taxation opportunities and as well as central government budgetary support for local state administration. This can be compared with the current and planned expenditures to determine the degree of financial and service provision efficiency.

An actors analysis elaborating in detail the particular interests of actors and their limitations in regard to project activities and partners should be the next step. The actors analysis could be undertaken as part of a Peace and Conflict analysis.

Guiding questions on status of local state administrations

- What are the exact roles and functions of the state administration, especially those most relevant for post conflict/ post disaster projects?

- What functions have been delegated from national and sub-national (Provincial) level to the local state administration?

- How is the state administration organised at the project area level? Are there offices and qualified personnel at the field level? Do they have access to resources?

- Which line departments have offices at field level and are there professional staff located at these levels?

Step 6: Analysing local, regional and national linkages and funding arrangements

The local state administration system is embedded into a whole hierarchy of administrative, legislative and executive correlations at the local, the sub-national and the national level. Understanding how the relationships are functioning is the key to being able to effectively focus capacity development assistance. Therefore a detailed analysis of power structures and roles, functions and inter-connections between the different organisations making up the local state administration is needed. At the same time this should result in an essential overview of how the linkages are to the next higher administrative level. Furthermore the analysis should look into the financial flows and command lines. In countries where some degree of decentralisation is planned or is in place it is very important to understand the whole decentralisation process in which roles and functions are often well spelled out.

However, while such a formal assessment will provide a good insight into how decisions are actually made, it is equally important to understand who really the key decision-makers are. This informal decision-making process is quite common and by understanding it the ability of the project can constructively integrate these key decision-makers through targeted capacity development measures. The analysis will also provide an insight into how the project could strengthen the formal decision-makers so that they are able to take over their functions with emphasis being centred on actual service efficiency. An ideal method for the process is SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats analysis).

Guiding questions on status of local state administrations

- Is there a good description available on the hierarchy of roles and functions (national, sub-national and local)?

- How are the three key issues, political, administrative and fiscal decentralisation, organised in the country?

Step 7: Examining the efficiency of current key service providers

The efficiency and effectiveness of the current local state administration is important to know not only as a determinant of service capability to the communities but also as this will provide ideas on where capacity development is required.

The SWOT analysis as carried out in Step 6 would measure the service efficiency along different parameters: the most basic being whether a service is being offered at all and at the other extreme it could include a cost efficiency calculation. Service efficiency could also be measured in terms of time it takes for communities to access a service (e.g. average time taken to reach a health clinic or average time it taken for addressing citizen complaint by the state administrations).

The reason for highlighting the efficiency aspects is that often only the physical availability of a state administration service provider is measured. There a are a number of different methods and tools available for measuring efficiency. One effective tool is the citizen report card method, in which the citizens are asked to comment and determine the efficiency of services. Other methods can be derived from typical economic methods such as cost benefit analysis. Capacity works does not have any method that specifically deals with economic efficiency of service providers.

Step 8: Assessment of other service providers in the local area

In most cases in the project areas there are also other international donor organisations, international non-governmental organisations, national non-governmental organisations working and private sector contractors working. Gaining an overview of the different organisations operating in the project area is necessary to coordinate the work of the post conflict/ post disaster projects project effectively and to derive synergies.

A simple overview matrix that lists the organisations working in the area, their mandate, main areas and sectors of operation would already be very useful. Analysing the organisations and determining their strengths and weaknesses can further refine the information. Much of the information may already exist, for example in the feasibility report of the project and/or reports by UNDP / OCHA and other UN organisations who are often mandated to compile a list of donor organisations. There may also be NGO forum that consolidates all information on NGOs working in the area.

Guiding questions on status of other donor organisations

- Is an overview available of all INGOs, NGOs, and donor organisations available who work in the project area?

- Is there an active formal or informal coordination between the local state administration and other development partners in place and operational?

3. Steps for developing CD measures

Core elements of capacity development

Capacity development is a holistic process through which people, organisations and societies mobilise, maintain, adapt and expand their ability to manage their own sustainable development. For post conflict/ post disaster projects capacity development is directed towards all actors involved in the rehabilitation or development of the socio-economic infra-structure, with emphasis on strengthening state administrations.

Post conflict/ post disaster projects undertake capacity development at all levels. For example, simple management tools or technical advisory services can be integrated into the capacity development of local staff or personnel from local state organisations. The capacity development is provided parallel to the provision of inputs depending upon the identified needs and requirements. These can take the form of seeds, building materials, as well as essential equipment, materials and possibly vehicles required to operate and manage basic office functions. Through this approach local capacities are systematically developed and strengthened. There are five core capabilities as part of capacity development (Brinkerhoff, D.W. 2007):

- The capability to self-organize: Communities and people are able to: mobilize resources (financial, human, organisational); create space and autonomy for independent action; motivate different partners; plan, decide, and engage collectively to address reconstruction, development and peace building needs.

- The capability to generate development results: Key stakeholders are able to: produce substantive outputs and outcomes (e.g. reconstruction of social and economic production factors such agricultural production, roads, markets, health systems, income generating opportunities).

- The capability to establish supportive relationships: Stakeholders can: establish and manage linkages, alliances, partnerships with others to leverage resources and actions; build legitimacy in the eyes of stakeholders; deal effectively with competition, politics, and power differentials.

The capability to adapt and self-renew: Stakeholders are able to: adapt and modify plans and operations based on monitoring of progress and outcomes; proactively anticipate change and new challenges; cope with shocks and develop resilience.

- The capability to achieve coherence: Stakeholders can: develop shared short and long-term strategies and visions; balance control, flexibility, and consistency; integrate and harmonize plans and actions in complex, multi-actor settings; and cope with cycles of stability and change.

Figure 3 depicts the four dimensions of failure that are commonly associated with fragile states with the five core components of capacity development. The lack of or limited capacity at the societal level is an important driver of fragility in a country. In many countries the unequal distribution of the capacities and capabilities is a further factor, with some groups in society being affected by exclusion from the social and economic development of the country.

Figure 3: Linking core capabilities to causes of fragility

Step 9: Elaboration of detailed capacity development concept

Developing a detailed capacity development concept outlining the areas to be supported by post conflict/ post disaster projects should be developed early on in the project. Essentially, capacity development presents the difference between existing knowledge and the required / desired knowledge and capacity. This presumes that a strategy or vision of what exactly is expected for improved state administrations is available (compare previous steps). The strategy provides the framework in which capacity development has to be undertaken and defines the know-how and capacity needs.

The capacity development strategy should make use of the results of the:

- Analysis of the legal and institutional framework conditions of local state administrations;

- Assessment of the roles, responsibilities and concrete tasks of organisations and the people working therein;

- Assessment of the required processes and mechanisms within and among organisations and stakeholders to achieve anticipated results;

- Identification of required knowledge, skills and attitudes of people in order to perform well.

The capacity development strategy defines the change requirements with regard to personal and organisational capacities, internal organisational processes and external system-wide mechanisms and processes.

Guiding questions on development of CD measures

- Are the results of the analysis of the capacity of state administrations completed and results known?

- Are the exact role and functions of the state administration known?

- When comparing the constraints of the state administration and the expected roles and functions can the CD measures be easily identified and defined?

- Can all important CD measures be realistically completed during the project duration?

Step 10: Analysing and determining potential local trainers

The next step in the process would be to establish a team of professional facilitators possessing sufficient local knowledge, skills and confidence to handle the challenges in promoting local state administrations and good local governance based on participatory and adult learning approaches.

The formation of groups of professional facilitators at the local level is one way of ensuring that professional training and advisory services can continue to be offered once the development programme has ended. Such a corps of local trainers is all the more important in rural areas where professional expertise is rare.

While training either professionals or trainers (through training of trainer courses), emphasis needs to be placed on building their capacities for process moderation within the context of the administrative reform processes. Reflection teams or small work-groups should be established to exchange experience, discuss issues and monitor the progress made on assignments given by the trainers.

Transfer of knowledge on decentralisation and local state administration related issues with particular reference to the country specific conditions.

- Transfer of skills on how to effectively handle the role of facilitators in the socio-cultural setting of the respective countries.

- Practising their new skills in specialised capacity building programmes.

- Peer group work to complete set tasks, to reflect on their own actions and to start develop their own concepts.

- Coaching and supervising trainees between formal training sessions.

Guiding questions on determining potential local trainers

- Is there a good and effective state training centre in the area that could provide CD training?

- Are there good professional trainers available in the area or at national level who could provide regular training?

- What needs to be done to institutionalise the training?

Step 11: Guiding implementation principles for projects

The implementation of the measures to strengthen local state administrations structures and organisations require that post conflict/ post disaster projects follow some basic principles. The following table 2 provides an overview of these basic principles as well as support questions:

Table 2: Guiding principles and examples of questions

Photo 2: Example of government departments providing capacity development for enterprise development at a buisness centre (source: GIZ-DETA)

4. Steps for implementing the CD measures

Step 12: Implementation of CD measures

This step involves the continuous implementation of the CD measures during the lifecycle of the post conflict/ post disaster projects whereby the objective is to ensure that the capacity development capability is institutionalised. This would then provide the basis upon which CD can be provided even after the project has come to an end. What may possibly seem to be quite logical is that the post conflict/ post disaster projects needs to keep close contacts with the local state administrations and needs to always make a conscious effort of strengthening and developing them, even when this may seem to be particularly challenging. Where the state administration is simply too weak, then the minimum should be to qualify and capacitate the state administration to undertake its coordination and oversight function. In these cases implementation may have to be sub-contracted to other organisations that have the necessary competencies.

Guiding questions on determining potential local trainers

- Are the CD measures included in the project plan of operations?

- Are sufficient project funds / resources available to implement the measures?

- Is the effectiveness of the CD measures being monitored and are the CD measures being re-planned on the basis of the results of the monitoring exercise?

- What is the level of satisfaction of the people participating in CD measures, are their expectations being met?

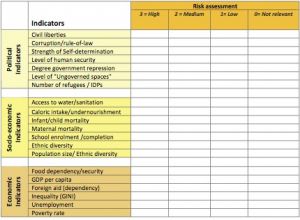

Step 13: Risk assessment and implementing M&E system

Capacity development in the context of post conflict/ post disaster projects has a number of risks and assumptions that must be permanently checked and considered. Many of these risks are related to the environment and framework conditions in which post conflict/ post disaster projects works and operates, especially when working in the context of fragile situations.

This can be observed or further assessed through a systematic set of indicators that can be correlated to the four main causes of fragility that have been elaborated above. Table 3 provides an example of how the external risk can be both assessed and monitored. In addition to these risks, post conflict/ post disaster projects also faces additional risks that are directly related to the way in which the programmes are designed. The main ones include:

- Limited time period of post conflict/ post disaster projects, which will only allow for a certain level of capacity development to be achieved.

- Flexibility required for quick action is often reduced by administrative procedures and formalities.

- Very weak state structures even bring limitations that cannot be overcome in the three-year implementation cycle of post conflict/ post disaster projects. Capacity development to overcome root causes of conflict or societal changes will take far longer. The risk here is that too high expectations will be levelled on projects that cannot be realistically met.

- Lack of political legitimacy of state administrations which cannot be overcome within 3 years requires that alternative forms of administration are developed to achieve the post conflict/ post disaster projects objectives.

- Local state administrations do not always have the populations interest as a core objective.

- The short-term planning horizons and limited or lack of resources (financial, human, etc.) on the part of the government.

- High staff turnovers within the projects, as well as state and civil society organisations.

- Inability to reach remote areas due to lack of or very poor infrastructure and these cannot be realistically repaired / built in the time frame of a normal post conflict/ post disaster projects.

- High levels of corruption.

- Overstretching capacity of the partner organisations through a proliferation of donors.

Table 3: Risk assessment matrix (example only)

|